Muskology is an overpopulated field. The compulsory purchase of Twitter by the world’s most advantaged alpha-dork has already been picked over from every possible angle, the near-universal conclusion being that he’s screwed up.

Waggish hubris has met contractual and pecuniary nemesis, resulting in petulance. Or, to put in Elon Musk’s preferred form:

Yet with Twitter stock scheduled for delisting today, are there any lessons left to learn from its less-than-a-decade of public life?

Possibly. Attempts to make money from microblogging predate Musk’s involvement by several years. A recap of what went wrong and when might help pinpoint why the newly installed Corn-Cob-in-Chief formed his many biases and blind spots.

Ideally, the process of reflection might also reveal a reverse Frankenstein: or how the machine created the monster, and how the monster will destroy the machine.

An @ElonMusk Twitter profile first appeared in early 2009, though it wasn’t him. The US election a year before had raised Twitter’s public profile enough to pull in celebrity CEOs including Jeff Bezos, Sundar Pichai and Mark Zuckerberg, as well as sparking speculation of interest from Google and Yahoo. But during the first stage of Twitter’s land-grab, Musk remained mostly offline and aloof.

He missed some fun. Twitter’s 2009-vintage “about” page offered the following warning:

How do you make money from Twitter?

Twitter has many appealing opportunities for generating revenue but we are holding off on implementation for now because we don’t want to distract ourselves from the more important work at hand which is to create a compelling service and great user experience for millions of people around the world. While our business model is in a research phase, we spend more money than we make.”

Also in early 2009, Bernstein Research star analyst Jeffrey Lindsay wrote about how Google or Yahoo buying Twitter would be an absolutely terrible idea:

Don’t get us wrong — we like Twitter and we think the concept of sending short open standard messages reporting on your activities is actually much more fun and more valuable than it sounds. The problem is that Twitter falls into the broad category of new internet businesses that are almost un-monetisable.

Lindsay’s 2009 guide to internet investing was to avoid social media. Sites without a niche would be bad at guessing their users’ specific wants without sucking down data in problematic volumes, he reasoned, so ads could only ever be intrusive. Users would resist paying for something previously given away free. The marketing and network effects of having celebrities onboard could easily reverse:

[Internet businesses that] make money can be described without referring to “future monetisation layers”, “deeply embedded value stacks”, “keeping it as a free tool” or “the 50 per cent of users who would definitely pay $5 per month for this”. The ones that do make money all seem to involve either mailing stuff to people who have paid for it online or getting advertising deals from the likes of General Motors.

One year later, with Twitter still independent thanks to bonfire money from VCs including Bezos Expeditions and Spark Capital, Musk took ownership of his namesake account. He started by posting fake quotes and name-dropping but promised to use Google+ for anything serious. Halcyon times.

The first viral tweet (in December 2011) was a joke stolen from Tina Fey. The second (in November 2013, the month of Twitter’s IPO) was to complain about media bias. The third (July 2014) was a nerd meme. The fourth (October 2014) was dick innuendo and so Musk’s persona had been formed awhole.

In-between, Twitter was valued at $14.2bn at IPO, or 44 times 2012 revenue ($317mm). By the end of the first session it was valued at $31bn, or 97 times revenue. This, the commentariat agreed, was nuts. Twitter was clunky, cold and unfriendly, particularly compared with Facebook, and was only able to sell its promoted content at flat fees. Its estimated 600 advertisers were spending on average just $30,000 each a year; Facebook was at the time earning $1mn per full-service client.

Twitter’s float was therefore predicated on Field of Dreams principle. Early research put ambitious multiples on its nascent video service (aka, Vine) and on MoPub, a mobile ads exchange Twitter bought shortly before IPO. (It was recently sold.) Data services were already in run-off and subscription fees were never mentioned, as it had been agreed long ago that customer tiers were anathema to scale. That left only adverts.

Here’s a revenue projection from Morgan Stanley’s 2013 initiation note:

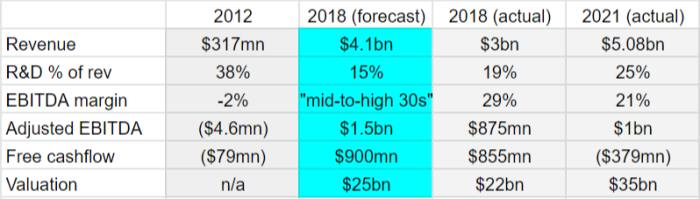

Pivotal analyst Brian Wieser reckoned Twitter could capture about 1 per cent of global ad spend ex China, justifying a $25bn valuation once the business reached maturity in 2018. What’s perhaps surprising is that his forecasts weren’t that far off.

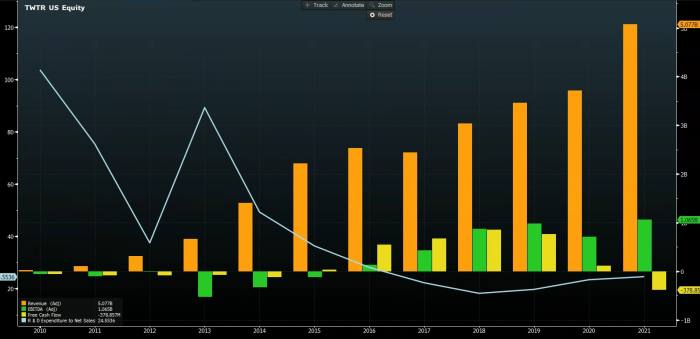

The below table shows Pivotal’s pre-float expectations versus actual performance; the chart below that, via Bloomberg, offers the big picture.

So Twitter grew revenue as expected, but failed to cap costs and therefore kept burning cash. That’s the story of the charts, but it’s not one investors will recognise. Quarter after quarter the company would disappoint the Street on sales, not expenses. Management had to constantly talk down expectations on ads. User numbers were always short of forecasts, partly on over-optimism but also because the definition of a user kept changing.

JPMorgan had guessed in its initiation research that the active user base would more than double to 500mn within five years; for the fourth quarter 2018, Twitter reported 126mn daily active users. Recent arguments about bot-counting have somehow overlooked all that, and that figuring out the audience size was proven to be almost completely pointless.

Twitter’s share price slid below the float price level in mid 2015 and remained underwater for another two years. There was a small recovery in 2017 as GAAP profitability moved on to the horizon, with video and livestreaming looking like they might be useful new products. But results remained weak and CEO Jack Dorsey’s eccentricities were causing disquiet.

It wasn’t until March 2020, shortly after Twitter pulled guidance on pandemic uncertainties, that the stock began to motor. The attractions of doom-scrolling meant user numbers were going up and advertisers had a literal captive audience. Price chart from Bloomberg:

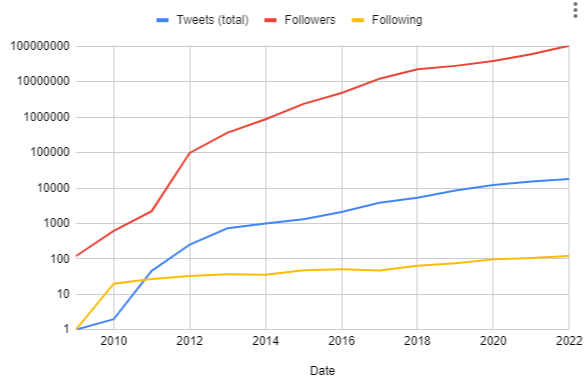

It’s worth comparing the above to a logarithmic perspective of Musk’s personal Twitter experience:

There are a few possible takeaways here. The first, and perhaps most obvious, is that Musk uses Twitter as a broadcast medium. His accounts followed took five years to double and another five years to double again. Musk only wants to listen when he’s being addressed, which is fair enough. He’s very busy, presumably, and very rich.

The second takeaway is that, unlike most Twitter users, Musk’s audience grows exponentially to his output. The tweet total has doubled about every two years, while the follower count doubled annually. For any attention vampire, this alone is a strongly positive ROCE that makes Twitter a good use of time and energy.

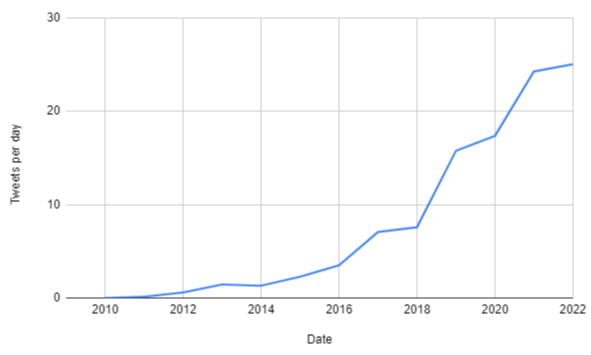

Tweets per day show that bird-app addiction had subsumed Musk’s personality by 2019, having first become problematic in around 2014.

Musk’s personal golden age of tweeting was 2014-18, which coincided with Twitter’s worst years as gauged by share price. Arriving late meant Musk missed the hope and the hype. Instead he caught only grinding corporate failure, which was largely framed around user targets, and the powerful social network effects, which were mostly political.

In that context, why wouldn’t Musk think he was better at Twitter than Twitter? Rapid audience growth though nerdery, agitation and mediocre shitposting was proving he could do what Dorsey couldn’t.

But Twitter’s problems as a public company were misdiagnosed. Revenue growth wasn’t far off initial targets, in spite of the quarterly agonising over ad metrics and active user counts. Where the IPO models were wrong was around costs. They went up, not down, because maintaining a comfort zone for advertisers turned out to be a perpetual expense that grew in proportion to the user base.

To be fair, Musk has attacked the cost issue with zeal. But not a lot of forethought. Whatever the motivations for bidding, his approach to running the business — the indiscriminate firings, the goading of the audience, the firebombing of the advertisers’ comfort zone — are from his atypical experience of the site.

History could’ve offered a clearer perspective on why, for example, charging $8 a month to watch a rich man humiliate himself isn’t the winning proposition imagined. But it seems that, during the months Musk was desperately trying not to buy Twitter, he was thinking only about what to tweet next.

Further reading:

Honestly, where to begin? For The Verge, Nilay Patel has a peerless overview. For the FT, Hannah Murphy and Ian Johnston give the inside track. Also for the FT, Marietje Schaake wraps up the regulatory angles. For Platformer, Casey Newton and Zoë Schiffer examine the job cuts. For Tocqueville21, Megan Jones dissects Elon’s personality. On Medium, Dave Troy has a collusion conspiracy theory. For Bloomberg, Matt Levine’s does piecework. On Twitter, Andrew Gawthorpe has the geopolitical conspiracy theory. And finally, there’s this tweet:

just occurred to me that the magnificence of the timeline this week is because this is a show about the most expensive mid life crisis ever, but narrated from the point of view of the sports car itself

— zatapatique (@zatapatique) November 6, 2022

Musk’s Bride of Reverse Frankentwitter Republished from Source https://www.ft.com/content/5ad79fea-a453-4700-9fc8-ceb326ce0fb8 via https://www.ft.com/companies/technology?format=rss

<!–

–>

- Bitcoin

- bizbuildermike

- blockchain

- blockchain compliance

- blockchain conference

- Blockchain Consultants

- coinbase

- coingenius

- Consensus

- crypto conference

- crypto mining

- cryptocurrency

- decentralized

- DeFi

- Digital Assets

- ethereum

- machine learning

- non fungible token

- plato

- plato ai

- Plato Data Intelligence

- Platoblockchain

- PlatoData

- platogaming

- Polygon

- proof of stake

- W3

- zephyrnet