Helen Gleeson, who chairs the Bell Burnell Graduate Scholarship Fund, describes the importance of nurturing and supporting talented students from non-traditional backgrounds in physics so they can overcome obstacles in academia

Imagine winning a $3m prize and then giving all the money away. That’s exactly what the astrophysicist Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell did in 2018, when she won the Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics for her 1967 discovery of pulsars and her “inspiring scientific leadership over the last five decades”.

Indeed, Bell Burnell donated further prize money in 2021, when she was awarded the world’s oldest scientific prize, the Royal Society Copley Medal. Rather than going to family or to an established charity, in both cases she used these gifts to set up the Bell Burnell Graduate Scholarship Fund, or BBGSF (see box below). It aims to help PhD students from groups that are under-represented in physics and is supported and administered by the Institute of Physics (IOP), which publishes Physics World.

‘Look happy dear, you’ve just made a discovery’

Bell Burnell is no stranger to the barriers faced by students from minority groups. She has confronted many herself, right from when she was a physics undergraduate at the University of Glasgow in the early 1960s. Already isolated by being the only woman left on her course by the final year, she was surrounded by male students who “stamped their feet, whistled, catcalled and made as much unpleasant noise as they could” every time she entered a lecture theatre.

Later, while building a radio telescope during her PhD at the University of Cambridge, male colleagues deemed the manual labour involved as “not suitable for a woman”, but Bell Burnell was quick to correct them and get involved in the construction work. Indeed, different barriers, often the result of societal expectations and norms within the physics community and beyond, challenged her throughout her career. Bell Burnell overcame them all and her achievements are nothing short of stellar.

The Bell Burnell Graduate Scholarship Fund: how it works

The Bell Burnell Graduate Scholarship Fund (BBGSF) supports PhD students from the UK and Ireland who come from groups that are under-represented in physics. It recognizes that the barriers encountered by some individuals can mean that, while they have the talent and enthusiasm for high-level study, they would either not be awarded a PhD scholarship via conventional schemes or would need additional support to complete their doctorate.

To apply, students must already be enrolled at – or have an offer from – a physics-based postgraduate doctoral programme at an eligible host university or institution in the UK, which will nominate candidates for the grant. The fund only support studies in a physics department or institute that has a Juno and/or Athena SWAN award at the time the student is being enrolled.

Students from minority groups in physics are eligible for a BBGSF scholarship. The under-represented groups in physics include women; students of Black-Caribbean, Black-African and other minority ethnic (BAME) heritage; students with disabilities or who require additional funding to support inclusive learning; LGBTQ+ students; and students from disadvantaged backgrounds who may struggle to find the levels of funding needed to complete their studies. People with qualifying refugee status who meet the above criteria are also encouraged to apply.

Since its launch in 2020, the fourth grant cycle is just now being completed, leading to:

- 128 applicants;

- 31 awards;

- more than £750,000 in awards being handed out.

Overcoming barriers

Many of us are not surprised by such tales of open hostility to women in physics in the past – after all, Bell Burnell was an undergraduate more than 50 years ago. But these days, when initiatives such as the Equality Challenge Unit’s Athena SWAN (Scientific Women’s Academic Network) charter and Project Juno – the IOP’s flagship gender-equality award for physics institutions – have brought many gender-related issues to the forefront and supported best practice across our community, surely such behaviour is a thing of the past? Are there really still significant barriers to people doing physics?

While the number of women studying physics at university in the UK has increased over the last 20 years, it is still too low at 23%. The picture is equally bad for many other groups. The proportion of physics students who come from low-income households is far smaller than it should be, and as for students from ethnic groups that are minorities in the UK, they are fewer still. This number will hopefully slowly increase as more women and minoritized groups trickle through the pipeline, but we can do more to help. You only have to read the inspiring stories of the 21 Bell Burnell Scholars we recruited in the first three rounds, to truly understand the many different challenges people still have to overcome today, to pursue a career in physics.

In 2019 I was invited to be chair of the BBGSF as it was being set up, and I’ve continued to oversee the fund, which is now into its fourth cycle. I’m supported by a hugely committed team who bring diverse skills and life experiences from many under-represented groups in physics – something that was vital in setting up this unique scheme.

In designing the operation of the BBGSF, we developed the following working principles:

- All candidates for a full grant must be co-funded by the host university or institution where the student is based. The idea here is to ensure that the university also has a vested interest in the success of the scheme.

- We recognize promise rather than absolute achievements in applicants. We don’t distinguish between someone who has achieved a three-year BSc or a four-year MPhys degree, nor do we attempt to make judgements on marks or rank. This is because barriers such as financial hardship can mean that some candidates simply can’t afford to do an MPhys, or their need to have a job alongside studying impacts their ability to study.

- We consider how the applicant could act as an ambassador for the BBGSF. We want to spread the word as much as we can, both about the fund and about our approach to facilitating diversity in graduate study.

- We consider the supervisory team, the PhD environment and immediate research culture, alongside the applicant. We expect that our scholars will be well supported scientifically, but we also want them to thrive as individuals, in an environment where they have support and a feeling of belonging, to maximize their chances of success.

- We want to inspire good practice in selecting PhD candidates. Indeed, we’re hoping that asking institutions to tell us how they select candidates will encourage them to reflect on how inclusive (or not) their processes are.

Beating bias, discrimination and marginalization

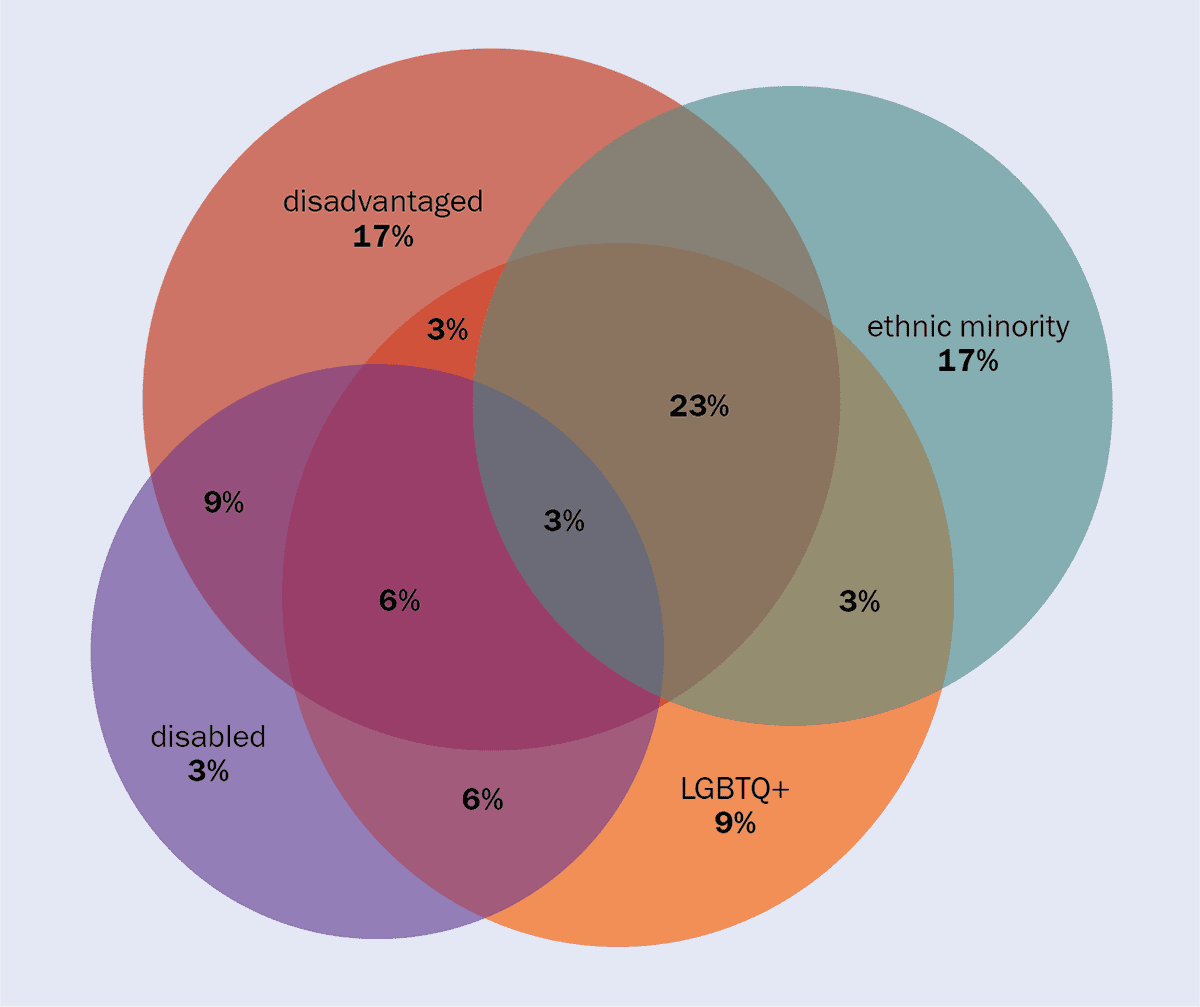

Some stark findings emerge when we analyse the different under-represented groups from which those applying for – and winning – BBGSF awards come. Perhaps the most striking thing after seeing the sheer number of highly qualified and motivated students who need our funding is the huge extent to which intersectionality comes into play. Of all the applicants in 2022 and 2023, 80% were women, 56% had disabilities, 56% came from disadvantaged backgrounds, 26% were LGBTQ+ and 46% came from ethnic minority groups. This is representative of the distribution we’ve seen in all applications so far, and is reflected in the population of our awardees (figure 1).

As a white woman who began my degree in 1980, I find it hard to imagine how much harder my career progression would have been if I’d suffered the double (or triple) whammy of multiple bias, discrimination or marginalization. However, this is the reality for many of our very capable undergraduates today.

For example, one of the BBGSF scholars told me (and I paraphrase), “The fact I’m a woman in physics has never been an issue – the problem has been that I’m ‘poor’. I had to hold down a job while doing my degree and my marks suffered because of that. Once, I was refused an extension to a deadline because the academic believed it was ‘my choice’ to have a job and that I should choose between being committed to my physics degree and getting more ‘pocket money’.” Many, if not most, academic physicists in the UK come from middle-class backgrounds and, by definition, few have experienced such hardship. This can lead to unconscious bias that is much broader and every bit as damaging as the gender bias we’re now relatively familiar with.

Criteria such as research experience, which is often used in awarding PhD scholarships, put a a PhD beyond the hope of otherwise excellent candidates. This is because students who have responsibilities such as being a carer, or who need to work throughout the holiday periods in an academic year, often cannot take up internships. Such students will therefore not have that “all-important” research experience, or have had the chance to write a paper – both of which often carry significant weight when PhD applications are being considered. Indeed, awarding PhD funding simply on the basis of academic achievement, such as exam grades, research experience or papers published, makes us miss excellent candidates and restricts the diversity of the physics community.

Beyond good intentions

I strongly believe that our community is mostly a caring one, where people aspire to be the best they can be. However, even in the applications to the BBGSF some academics miss the point, well-intentioned though they may seem. For example, we’ve heard comments like “My commitment as a PhD supervisor to supporting minorities is clear because I’ve just employed a non-white, female postdoctoral research assistant – she will be ideal in supervising this student.” Or “We considered all eligible students and chose the one with the top marks.” Token gestures such as these can sometimes do more harm than good, and will not, in the long run, drive the change that we want: to truly champion students from all walks of life in physics.

More worryingly, some bad behaviour is pervasive. I’ve had to reassure some of our scholars that it is not okay to be shouted at, no matter what the situation, and have given them advice on how to manage such behaviour. Unfortunately, quite a few PhD students and early-career researchers face this kind of problem, irrespective of whether they are from an under-represented group – but that doesn’t make it okay. And it’s definitely not okay to have other senior figures then excuse such behaviour by saying “Don’t worry about it – it’s just how professor X is – they shout at everyone.” We should be moving away from such conduct altogether.

I’ve also had to intervene with institutions that require PhD students to buy their own laptop or computer, which can cost almost a month’s worth of their stipend. If a department really cannot afford to equip its PhD students with computing hardware, the BBGSF contributes to the students’ research expenses with funds that can be used for such purchases. Ironically, though, it’s often the richest universities that have this expectation that students should pay for their own laptops.

Despite these issues, we are hugely grateful for the support that physics departments and institutes across the UK and Ireland have given the scheme, by being willing to co-fund scholars. Some have even gone beyond the co-funding requested. One particular physics department committed to fully funding the applicants it put forward – irrespective of the outcome of their application to the BBGSF – because it could see the value of increasing diversity and supporting students with great promise. Another worked with us to find the majority of the funding for a student as we had hit the top of our budget. We also provide fully funded top-up awards that allow PhD students to balance their research duties with any caring responsibilities, or give them money to complete their PhD when all other sources fail.

Personal and professional impact

Being chair of the BBGSF has been both a privilege and a life lesson. The very existence of the BBGSF has given students a reason to approach someone with questions about funding, as well as the confidence to do so. After one particular talk I gave about our scheme, I ended up in a long discussion with a disabled student. They were self-funding a PhD because they needed to study part-time and had been told that it wasn’t possible to hold a UKRI scholarship part-time. It was also unclear to them whether the BBGSF fund supports part-time applications – which we do. When I looked into this, I found conflicting advice about part-time UKRI funding for PhDs, but I was able to clarify that it is possible to hold UKRI studentships part-time. This crucial information has now been made clearer on the UKRI website and hopefully the option of part-time PhDs will be advertised more widely across institutions in the future.

The fund is making a real difference. Our 10-year plan is to have a cohort of 100 BBGSF scholars, and we’re well on the way to that. The IOP has been vigorously fundraising, and we are incredibly grateful for all the donations that have made it possible for us to increase the number of awards made, from four in 2020 to nine in 2022.

With her generosity, Jocelyn Bell Burnell started something special. She not only understands the value of diversity to our community, but has done amazing things to foster it

Because we immediately and unilaterally matched the increase to PhD stipends announced by the UKRI in October 2022, it does unfortunately mean there might be a fall in the number of awards we can make this year. But we always hope for more donors to the fund – big or small.

With her own incredible generosity, Bell Burnell has started something truly special. She not only understands the value of diversity to our community, but has done amazing things to foster it. The clapping and stamping when she enters a lecture theatre these days is, thankfully, for a very different reason – one of immense gratitude and support.

- The Bell Burnell Graduate Scholarship Fund can be contacted at bellburnellfund@iop.org. The next round of the Bell Burnell Graduate Scholarship Fund will open for applications in autumn 2023. For information on how to apply and to read interviews with previous awardees, see our website

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Minting the Future w Adryenn Ashley. Access Here.

- Source: https://physicsworld.com/a/breaking-barriers-and-opening-up-physics-the-growing-impact-of-the-bell-burnell-graduate-scholarship-fund/

- :has

- :is

- :not

- ][p

- $UP

- 000

- 1

- 100

- 20

- 20 years

- 2018

- 2019

- 2020

- 2021

- 2022

- 2023

- 26%

- 50 Years

- a

- ability

- Able

- About

- about IT

- above

- Absolute

- AC

- academic

- achieved

- achievement

- achievements

- across

- Act

- Additional

- administered

- advice

- After

- AG

- AI

- aims

- All

- alongside

- already

- also

- always

- amazing

- Ambassador

- an

- analyse

- analysis

- and

- announced

- Another

- any

- Application

- applications

- Apply

- Applying

- approach

- ARE

- AS

- Assistant

- At

- award

- awarded

- awards

- backgrounds

- Bad

- Balance

- barriers

- based

- basis

- BE

- because

- been

- began

- being

- believe

- believed

- Bell

- below

- BEST

- between

- Beyond

- bias

- Big

- Bit

- both

- Box

- Breaking

- breakthrough

- bring

- broader

- brought

- BSC

- budget

- Building

- buy

- by

- cambridge

- CAN

- candidates

- cannot

- capable

- Career

- carry

- cases

- Celebration

- centre

- Chair

- challenge

- challenged

- challenges

- champion

- Chance

- chances

- change

- Charity

- Chart

- Choose

- chose

- clear

- clearer

- click

- Cohort

- colleagues

- come

- comments

- commitment

- committed

- community

- complete

- Completed

- computer

- computing

- Conduct

- confidence

- Conflicting

- Consider

- considered

- construction

- continued

- conventional

- Cost

- could

- Course

- criteria

- crucial

- Culture

- cycle

- damaging

- data

- Days

- deadline

- definitely

- Degree

- Department

- departments

- designing

- developed

- DID

- difference

- different

- disabilities

- disabled

- discovery

- discussion

- distinguish

- distribution

- diverse

- Diversity

- Doesn’t

- doing

- donations

- Dont

- double

- down

- drive

- e

- Early

- either

- eligible

- encourage

- encouraged

- enjoy

- enrolled

- ensure

- entered

- Enters

- enthusiasm

- Environment

- equality

- equally

- established

- Even

- Event

- Every

- everyone

- exactly

- exam

- example

- excellent

- expect

- expectation

- expectations

- expenses

- experience

- experienced

- Experiences

- extension

- Face

- faced

- facilitating

- FAIL

- Fall

- familiar

- family

- Feet

- female

- few

- Figure

- Figures

- final

- financial

- Find

- First

- flagship

- flow

- following

- For

- forefront

- Forward

- Foster

- found

- four

- Fourth

- from

- full

- fully

- fund

- fundamental

- funded

- funding

- Fundraising

- funds

- further

- future

- Gender

- get

- getting

- gifts

- Give

- given

- Giving

- going

- good

- GP

- graduate

- grant

- grateful

- gratitude

- great

- Group

- Group’s

- Growing

- happy

- Hard

- hardship

- Hardware

- Have

- Headquarters

- heard

- Held

- help

- helped

- here

- heritage

- high-level

- highly

- Hit

- hold

- Holiday

- hope

- Hopefully

- hoping

- host

- households

- How

- How To

- However

- http

- HTTPS

- huge

- Hugely

- i

- idea

- ideal

- image

- imagine

- immediate

- immediately

- immense

- Impact

- Impacts

- importance

- in

- include

- Inclusive

- Increase

- increased

- increasing

- incredible

- incredibly

- individuals

- information

- initiatives

- inspire

- inspiring

- Institute

- Institution

- institutions

- interest

- internships

- intervene

- Interviews

- into

- involved

- ireland

- Ironically

- irrespective

- isolated

- issue

- issues

- IT

- ITS

- Job

- joined

- jpg

- Kind

- Labour

- laptop

- laptops

- Last

- launch

- lead

- Leadership

- leading

- learning

- Lecture

- lesson

- levels

- Life

- like

- Long

- looked

- Low

- made

- Majority

- make

- MAKES

- Making

- manage

- manual

- many

- matched

- Matter

- max-width

- Maximize

- May..

- Meet

- might

- minorities

- minority

- money

- more

- most

- motivated

- moving

- multiple

- Need

- needed

- network

- next

- Noise

- Nominate

- now

- number

- obstacles

- october

- of

- offer

- Okay

- oldest

- on

- ONE

- only

- open

- opening

- operation

- Option

- or

- Other

- otherwise

- our

- Outcome

- over

- Overcome

- own

- panel

- Paper

- papers

- particular

- past

- Pay

- People

- perhaps

- periods

- PhDs

- Physics

- picture

- pipeline

- plan

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Play

- Point

- population

- possible

- postgraduate

- practice

- previous

- principles

- prize

- Problem

- process

- processes

- professional

- Professor

- programme

- progression

- promise

- proportion

- provide

- published

- Publishes

- Publishing

- purchases

- put

- qualified

- qualifying

- Questions

- Quick

- Radio

- rather

- Read

- real

- Reality

- really

- reason

- recognize

- recognizes

- reflect

- reflected

- refugee

- relatively

- representative

- require

- research

- researchers

- responsibilities

- result

- round

- rounds

- royal

- Run

- s

- scheme

- schemes

- Scholars

- scientific

- seeing

- selecting

- senior

- serves

- set

- setting

- Short

- should

- shown

- Shows

- significant

- simply

- since

- situation

- skills

- Slowly

- small

- smaller

- So

- so Far

- societal

- Society

- some

- Someone

- something

- Sources

- special

- spread

- stark

- started

- Status

- Stellar

- Still

- Stories

- stranger

- strongly

- Struggle

- Student

- Students

- studies

- Study

- Studying

- success

- such

- suitable

- supplied

- support

- Supported

- Supporting

- Supports

- surely

- surprised

- surrounded

- swan

- Take

- Talent

- talented

- Talk

- Tea

- team

- than

- Thankfully

- that

- The

- The Future

- the UK

- theatre

- their

- Them

- therefore

- These

- thing

- things

- this

- this year

- three

- Thrive

- Through

- throughout

- thumbnail

- time

- to

- today

- token

- too

- top

- Triple

- true

- Uk

- understand

- understands

- unique

- Universities

- university

- university of cambridge

- us

- used

- value

- various

- via

- vital

- W

- was

- Way..

- we

- Website

- weight

- WELL

- were

- What

- whether

- which

- while

- white

- WHO

- widely

- will

- willing

- winning

- with

- within

- woman

- Women

- Won

- Word

- Work

- worked

- working

- world’s

- worth

- would

- write

- X

- year

- years

- You

- zephyrnet