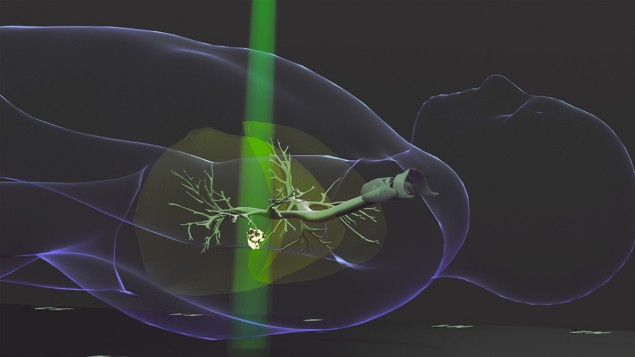

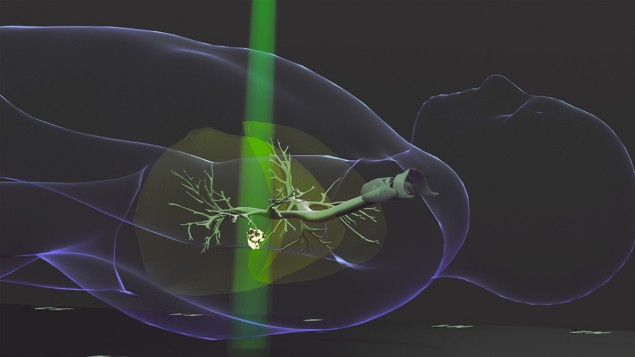

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) is a precision cancer treatment that delivers highly focused, intense radiation doses over just a few treatment sessions. Also known as stereotactic body radiation therapy, SABR is the standard-of-care for inoperable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, it can confer a higher risk of severe-to-potentially fatal toxicities than more conventionally delivered radiotherapy

To minimize such risks, researchers at Stanford University have developed an individualized approach for lung SABR, using dose and fractionation regimens based on tumour volume, location and histologic findings. Their strategy and clinical trial, described in JAMA Oncology, produced excellent local control with few toxic effects for its 217 participants.

“The iSABR [individualized SABR] trial demonstrated that we can personalize treatment to the characteristics of individual patients to optimize the clinical outcomes by balancing effective control of lung tumours with minimizing side effects,” explains Billy Loo Jr, co-principal investigator of the trial along with Maximilian Diehn. “In prior studies, these factors impacted the likelihood of the tumours being controlled by SABR, or the risk of serious normal organ injury by SABR. By individualizing treatment according to these factors, we hypothesized the impact of these factors could be overcome.”

In their phase 2 non-randomized trial, the researchers enrolled 214 patients at Stanford and three at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan. Patients were categorized into three groups: those with a single NSCLC (group 1); those having a new primary NSCLC with a history of prior NSCLC or having multiple NSCLCs (group 2); and those with lung metastases from NSCLC or another solid tumour (group 3).

Based on tumour volume and location, the researchers designed five dose-and-fractionation schedules, with up to four tumours treated with once-daily SABR. Doses ranged from 25 Gy in one fraction (for 55% of the patients) to 60 Gy in eight fractions. Large tumours received higher doses, while central tumours generally received a lower dose per fraction.

For smaller tumours, with a volume of 10 cm3 or less, the researchers prescribed a biologically effective dose (BED10) of 80–87.5 Gy, lower than the standard dose of 100 Gy BED10. All other regimens had BED10 greater than 100 Gy. Patients with colorectal metastases (which exhibit radioresistance) received at least 50 Gy in four fractions.

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 33 months. Of the 285 treated tumours, 26 (or 9%) had a local recurrence. Freedom from local recurrence at one year was 97%, 94% and 96% for patients in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively, confirming the hypothesis that the one-year local recurrence risk was less than 20% for each of the groups. At two years, freedom from local recurrence ranged from 90% in group 1 to 95% in group 3, and at five years it ranged from 83% in group 1 to 93% in group 2. The cumulative incidence of treated-tumour recurrence for all participants was 3% at one year, 5% at two years and 7% at five years.

Compared with published clinical trials of patients prescribed standard doses without individualization, fewer patients in this study experienced side effects, and these were much less severe than those previously reported. Sixteen patients developed grade 2 or higher pneumonitis, 13 had noncardiac chest pain and five had pleural effusion. Only four patients experienced grade 4 toxicities and one patient had a grade 5 adverse event. The researchers report that the risk of more severe toxic effects was higher in patients with ultracentral tumours.

Future prospects

In an accompanying invited commentary in JAMA Oncology, Vivek Verma from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center writes that “very few prospective trials have attempted to reduce BEDs”. He notes that “among the most common misconceptions of lung SABR is that virtually all patients experience high local control”. As a result, many radiation oncologists reflexively prescribe 100 Gy10 (50 Gy in five fractions) for virtually all lung SABR cases. “In reality, the dogmatic 100 Gy10 BED threshold is merely based on retrospective data. It is essential to understand there is an interplay between tumour size/histologic type and the BED required for durable local control,” Verma writes.

The researchers are currently conducting a clinical trial (ADAPT-E) in which patients with early-stage lung cancer are selected for adjuvant treatment with immunotherapy following their initial treatment with SABR or surgery, based on whether there is evidence of microscopic residual cancer detected by an ultrasensitive assay for circulating tumour DNA in the blood.

Assessing tumour hypoxia could personalize lung cancer treatments

“Diehn’s laboratory is developing ultrasensitive novel assays for circulating tumour DNA and also identified the KEAP1/NFE2L2 pathway as a radioresistance mechanism,” Loo tells Physics World. “We know that the genetic characteristics of tumours can also determine their response to therapy. Prior work has demonstrated that approximately half of the local tumour recurrences following radiotherapy might be explained by mutations in the KEAP1/NFE2L2 gene pathway that lead to ramping up the tumour cells’ antioxidant defences against radiation damage.”

Loo adds that his team is also studying the biological effects of FLASH therapy, the delivery of ultrahigh dose rates in a fraction of a second. “FLASH therapy has been shown in preclinical research to reduce damage to normal tissues without compromising tumour control. My colleagues and I are developing new technology to translate FLASH treatment to clinical use and to be able to optimize clinical outcomes even more in the future.”

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://physicsworld.com/a/personalized-lung-cancer-radiotherapy-proves-safer-more-effective/

- :has

- :is

- $UP

- 1

- 10

- 100

- 13

- 160

- 214

- 25

- 26%

- 33

- 50

- 60

- 95%

- a

- Able

- AC

- According

- Adds

- adverse

- against

- All

- along

- also

- an

- and

- anderson

- Another

- approach

- approximately

- ARE

- AS

- At

- attempted

- balancing

- based

- BE

- been

- being

- between

- blood

- body

- by

- CAN

- Cancer

- Cancer Treatment

- cases

- Center

- central

- characteristics

- circulating

- Clinical

- clinical trials

- colleagues

- Common

- compromising

- conducting

- control

- controlled

- could

- Currently

- damage

- data

- delivered

- delivers

- delivery

- demonstrated

- described

- designed

- detected

- Determine

- developed

- developing

- dna

- dose

- each

- early stage

- Effective

- effects

- enrolled

- essential

- Even

- Event

- evidence

- excellent

- exhibit

- experience

- experienced

- explained

- Explains

- factors

- few

- fewer

- findings

- five

- Flash

- focused

- followed

- following

- For

- four

- fraction

- Freedom

- from

- future

- generally

- genetic

- Global

- grade

- greater

- Group

- Group’s

- had

- Half

- Have

- having

- he

- High

- higher

- highly

- his

- history

- However

- HTTPS

- i

- identified

- image

- Immunotherapy

- Impact

- impacted

- in

- incidence

- individual

- information

- initial

- into

- invited

- issue

- IT

- ITS

- Japan

- jp

- jpg

- just

- Know

- known

- laboratory

- large

- lead

- least

- less

- less than 20%

- likelihood

- local

- location

- Low

- lower

- many

- max-width

- mechanism

- merely

- might

- minimizing

- misconceptions

- months

- more

- most

- much

- multiple

- my

- New

- normal

- Notes

- novel

- of

- on

- ONE

- only

- Optimize

- or

- Other

- outcomes

- over

- Overcome

- Pain

- participants

- pathway

- patient

- patients

- per

- personalize

- Personalized

- phase

- Physics

- Physics World

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Precision

- prescribe

- previously

- primary

- Prior

- Produced

- prospective

- proves

- provides

- published

- Radiotherapy

- ramping

- Rates

- Reality

- received

- recurrence

- reduce

- report

- Reported

- required

- research

- researchers

- respectively

- response

- result

- Risk

- risks

- safer

- Second

- selected

- serious

- sessions

- severe

- shown

- side

- single

- smaller

- solid

- standard

- stanford

- Strategy

- studies

- Study

- Studying

- such

- Surgery

- Target

- team

- Technology

- texas

- than

- that

- The

- The Future

- their

- There.

- These

- this

- those

- three

- threshold

- thumbnail

- to

- treatment

- trial

- trials

- true

- two

- type

- understand

- university

- using

- virtually

- volume

- volumes

- was

- we

- were

- whether

- which

- while

- with

- without

- Work

- world

- year

- years

- zephyrnet