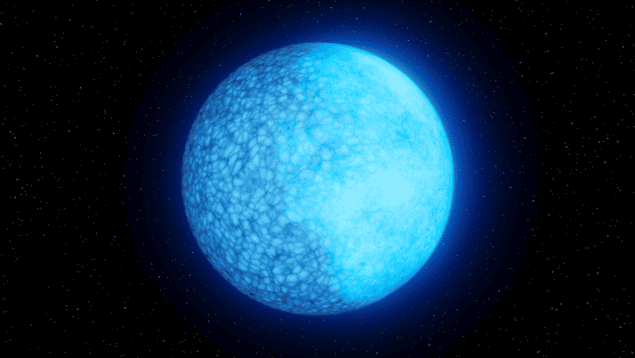

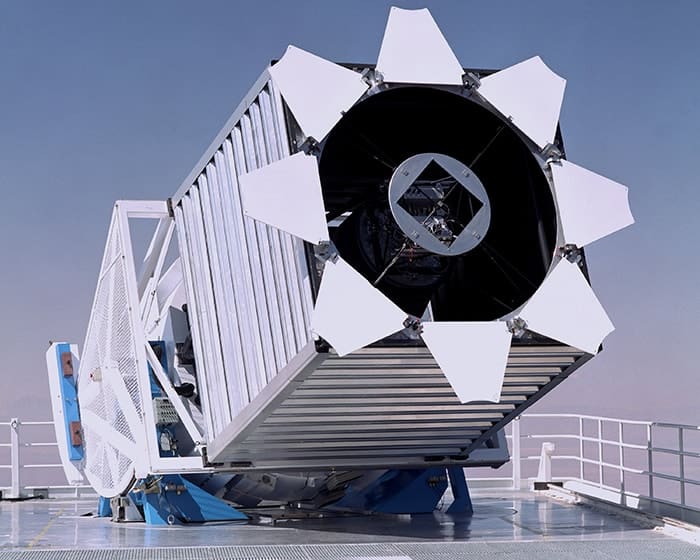

A rapidly rotating white dwarf star that contains two opposing hemispheres – one covered by hydrogen and the other by helium – has astronomers scratching their heads over how it got that way. The star, nicknamed “Janus” after the two-faced Roman god of transition, was discovered by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at Palomar Observatory in the US, and one possible explanation is that it is the result of a strong but lopsided magnetic field generated by the merger of two white dwarfs.

White dwarfs are the remains of Sun-like stars that have ceased nuclear reactions in their interiors, puffed off their outer layers, and experienced gravitational contraction of their remnant cores. The resulting objects are about the size of Earth, but with the mass of a star.

Though white dwarfs are born hot, they gradually cool as they age. This cooling affects their structure. At temperatures above 35,000 K, their surfaces are covered by a layer of hydrogen that envelops a sub-layer of helium. Once the surface temperature cools to 35,000–25,000 K (the exact temperature depends on the star’s mass), this helium layer begins to convect. If the upper hydrogen layer is thin enough, it can dissipate in the roiling helium.

About 40% of white dwarfs have made this transition from hydrogen dominance to helium dominance. However, since the transition normally occurs in a matter of seconds, no one has ever seen it happening – until, perhaps, now.

Stuck in transition?

Officially designated ZTF J203349.8+322901.1 (the numbers are its right ascension and declination co-ordinates on the sky) and located over 1300 light-years away, the Janus white dwarf attracted the attention of the California Institute of Technology astrophysicist Ilaria Caiazzo because of its rapid changes in brightness. Additional observations by Palomar and other facilities showed that the star completes one rotation every 15 minutes, during which its brightness varies from a maximum when its hydrogen-covered face is pointed towards Earth, to a minimum when we see the opposing hemisphere covered in helium.

The question is, why? “We might have finally caught a white dwarf in the act of transitioning,” Caiazzo tells Physics World. In fact, based on the findings of the team Caiazzo assembled to investigate the discovery, Janus seems to have got stuck in transition. On one of its hemispheres, helium convection seems to have consumed the hydrogen, but mysteriously the same does not appear to have occurred on the other. Writing in Nature, the team suggests that a sufficiently strong magnetic field offset from the white dwarf’s centre could be inhibiting helium convection on one hemisphere and not the other, but this explanation is tentative. Suffice to say, nobody has ever seen a white dwarf of two halves before.

“There’s no model that predicts this,” says team member Pier-Emmanuel Treblay, an astronomer at the University of Warwick, UK. “In astrophysics, when something is messed up and needs to be finely tuned, people often invoke magnetic fields, and this is a perfect example of that.”

About 20% of white dwarfs are magnetic, and some have field strengths of up to 1 billion Gauss. By comparison, Earth’s magnetic field is half a Gauss, while the magnetic field strength on the surface of the Sun is about one Gauss. For Janus, the team estimates the field must be 1000–1 million Gauss. Any stronger, and it would distort the star’s spectral lines.

“For Janus, we assume that there is a magnetic field because it would be very hard to explain the different composition on the two faces otherwise,” Caiazzo says. However, she adds, “We still don’t know why only some white dwarfs are magnetic and where this huge diversity in field strengths comes from.”

A white-dwarf merger?

Janus’ strong and lopsided magnetic field, its rapid rotation rate, its high mass (between 1.20 and 1.27 solar masses) and its two-faced composition all point to a quite remarkable white dwarf. For Tremblay, this indicates that other factors may be at play. “There must be something special about this white dwarf in addition to a magnetic field,” he says.

Tremblay speculates that Janus could have formed through the merger of two white dwarfs – an event that could have created internal magnetic dynamos. “The fast rotation, and the magnetic field generation and asymmetry, they all point to binary evolution and a merger,” he says.

Tremblay is also sceptical about the magnetic field being an offset dipole. The internal magnetic field structure of white dwarf stars is not yet well understood, and in his view, invoking an offset dipole could hide a higher-order magnetic field geometry.

White dwarf with nearly pure oxygen atmosphere surprises astronomers

“In my opinion, it means that the magnetic field might not be dipolar,” Tremblay says. “Instead it might be a quadrupole, with four poles, for example. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the field is offset from the centre.”

Implications for distance measurements

When white dwarfs explode as type Ia supernovae, their well-understood brightness allows astronomers to treat them as standard candles – a vital tool for measuring distances across the cosmos and the expansion rate of the universe. However, astronomers are still not sure how many type Ia supernovae occur when a single white dwarf accretes too much matter from a companion star and explodes, and how many occur due to the merger of two white dwarfs that, when combined, exceed the Chandrasekhar mass limit of 1.44 solar masses and explode.

If Janus is indeed the product of a merger of two smaller white dwarfs, finding more examples of half-transitioned white dwarfs will enable astronomers to constrain the numbers of such systems and how much they might contribute to the population of type Ia supernovae.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://physicsworld.com/a/two-faced-white-dwarf-star-leaves-astronomers-puzzled/

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- $UP

- 000

- 1

- 15%

- 20

- 27

- a

- About

- above

- AC

- across

- Act

- addition

- Additional

- Adds

- After

- age

- All

- allows

- also

- an

- and

- any

- appear

- ARE

- artist

- AS

- assembled

- assume

- At

- Atmosphere

- attention

- attracted

- away

- ball

- based

- BE

- because

- before

- being

- between

- Billion

- born

- but

- by

- california

- CAN

- Candles

- caught

- centre

- Changes

- COM

- combined

- comes

- companion

- comparison

- Completes

- consumed

- contains

- contraction

- contribute

- Cool

- Cosmos

- could

- covered

- created

- darker

- depends

- designated

- different

- digital

- discovered

- discovery

- distance

- Diversity

- does

- Doesn’t

- Dominance

- Dont

- due

- during

- earth

- enable

- enough

- estimates

- Event

- EVER

- Every

- evolution

- example

- examples

- exceed

- expansion

- experienced

- Explain

- explanation

- Explodes

- Face

- faces

- facilities

- fact

- factors

- FAST

- field

- Fields

- Finally

- finding

- findings

- For

- formed

- four

- from

- generated

- generation

- God

- gradually

- gravitational

- Half

- Happening

- Hard

- Have

- he

- heads

- helium

- hemispheres

- Hide

- High

- his

- HOT

- How

- However

- HTTPS

- huge

- hydrogen

- ia

- if

- image

- in

- indeed

- indicates

- information

- Institute

- internal

- investigate

- issue

- IT

- ITS

- jpg

- Know

- layer

- layers

- LIMIT

- lines

- located

- made

- Magnetic field

- many

- Mass

- masses

- Matter

- max-width

- maximum

- May..

- mean

- means

- measuring

- member

- Merger

- might

- Miller

- million

- minimum

- Minutes

- model

- more

- much

- must

- my

- Nature

- nearly

- necessarily

- needs

- no

- normally

- now

- nuclear

- numbers

- objects

- observatory

- occurred

- of

- off

- offset

- often

- on

- once

- ONE

- only

- Opinion

- Other

- otherwise

- over

- Oxygen

- People

- perfect

- perhaps

- Physics

- Physics World

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Play

- Point

- population

- possible

- Predicts

- Product

- question

- rapid

- rapidly

- Rate

- reactions

- remains

- remarkable

- result

- resulting

- right

- s

- same

- say

- says

- seconds

- see

- seems

- seen

- she

- showed

- Shows

- side

- since

- single

- Size

- Sky

- smaller

- solar

- some

- something

- special

- Spectral

- standard

- Star

- Stars

- Still

- strength

- strengths

- strong

- stronger

- structure

- such

- Suggests

- Sun

- sure

- Surface

- surprises

- Survey

- Systems

- team

- Technology

- telescope

- tells

- than

- that

- The

- their

- Them

- There.

- they

- this

- Through

- thumbnail

- to

- too

- tool

- towards

- transition

- transitioning

- treat

- true

- two

- type

- Uk

- understood

- Universe

- university

- until

- us

- very

- View

- vital

- was

- Way..

- we

- WELL

- when

- which

- while

- white

- White Dwarf

- why

- will

- with

- world

- would

- writing

- yet

- zephyrnet